Report about the 11th International Women Artist and Activist Festival, 15-21 May 2023, Prishtina & Mitrovica, Kosovo

FemArt & Me:

Report about the 11th International Women Artist and Activist Festival, 15-21 May 2023, Prishtina & Mitrovica, Kosovo

Clara Lhullier

As early as 1791, Olympe de Gouges wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Women and of the Female Citizen to raise attention to the unequal position of women in the French Revolution’s statement of equality. Although centuries later, the 11th edition of FemArt Festival reminds us that many of De Gouges’ claims remain timeless. Taking place on days 3 and 5 of the festival, the performance Olympe et Moi with the French actress Veronique Ataly connected current feminist struggles with those already present in De Gouges’ writings many years earlier. Through her monologue, the actress recounted her intimate journey in daring to question patriarchal norms. As the story’s thread brings De Gourges’ ideas to contemporary times, it not only pays tribute to the latter’s courage to confront the French regime but also to women who dare to fight for their emancipation in the present day.

The 11th edition of FemArt Festival in Prishtina and Mitrovica is an expression of this collective feminist effort. With the motto “Burn your fear”, the festival relies on women’s courage to re-claim their emancipation, and on expressions of difference to build bridges between each other. From 15-21 May 2023, activists joined artists from the region and beyond, and met in Kosovo to speak together through theater shows, panel discussions, exhibitions, conferences, performances, workshops, songs, and dance. Through their narratives and fictional stories, they have raised attention to instances where feminists had the courage to say enough to patriarchal violence and prejudice. Rather, they relied upon their collective initiatives to free themselves. What is more, FemArt 11 also constituted a testimony of love as a way to fight such battles and as a vehicle of social change: love for oneself, but also sisterhood love among each other.

Not by chance, my personal experience at FemArt is also narrated against this backdrop. It was through activists’ networks of solidarity that I, a young Brazilian feminist, embarked on a journey from Belgrade to Prishtina. While undeniably feeling a bit nervous at the beginning, it took me no more than a few hours to feel like I had known the feminist activists and artists who surrounded me for a long time: I felt at home with them, even if we had just met. As I write this article while thinking about my experience there, I realize there were two possible reasons for this. Curiously enough, part of this feeling of being close to each other was also created by their joy and excitement every time I mentioned I was from Brazil. After all the hugs and laughs that followed their first reaction, I even felt like I was actually in Brazil! While six years have passed since I left my home country, perhaps this was the first time I gave a second thought about where I am from and started coming to terms with some of the painful experiences which led me to move abroad.

The second reason was that the narratives and lived experiences shared during the festival quickly brought about feelings of solidarity among us. Despite my foreign background and young age, words, music, and artistic expression from the events resonated with me, and in a way also talked about my personal story as a feminist through the eyes, the bodies, and the voices of other women. At the same time, I also was moved by the expressions of sisterhood shared by anti-war feminist activists which have endured despite the most adverse conditions of the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. Through these re-encounters, I witnessed how feminist festivals in Sarajevo, Ljubljana, Belgrade, Prishtina, Zagreb, and Skopje were also an expression of long-term friendships that have been cultivated across borders.

Faced with the divisive ethno-nationalist politics and with feelings of helplessness, guilt, and responsibility for the crimes committed in their names during the last two decades of the twentieth century, feminist activists realized their pain was also political. For example, feminists in Belgrade stood up against the Serbian regime’s policy to create anti-war activities, organizations, artistic initiatives, and political movements. Such peace networks of mutual support and solidarity were vital for women in the former Yugoslavia to resist growing patriarchal backlash and militarism by caring and thinking about each other. As Lepa Mladjenović, anti-war feminist activist from Serbia recounted, “Feminists were deeply involved in the anti-war activities. Some of us were preparing packages for women living in no-electricity, no-water, no-heating Sarajevo with warm dedication, searching the shops to get only the particular food items that were allowed to be packed”.

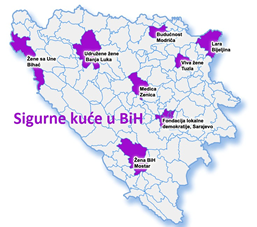

Among these initiatives, the Belgrade-based group Women in Black Against War built a long-term trajectory of anti-war actions that remains active to this day. Importantly, before, they have stood in solidarity with Kosovar Albanian women with the political message ALBANIAN WOMEN ARE OUR SISTERS, which opened a gate for sisterhood and later led to a Women’s Peace Coalition with Kosovo’s Women Network in 2006. While the Women in Black consolidated a transnational network over the years and continued to gather in public spaces and advocate for change, feminist festivals in the region also started to pop up as spaces where art and activism could meet and overcome barriers left from the war. Starting from the 2000s, some of these initiatives were Red Dawns in Slovenia (2001), PitchWise in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2005), Vox Feminae in Croatia (2007), BeFem in Serbia (2009), and FemArt in Kosovo (2012).

When it comes to women’s alliances between Serbia and Kosovo, art as activism also functioned as a political tool to engage in peacebuilding and transitional justice processes. Indeed, FemArt – Festival of Women’s Art and Activism was first created eleven years ago with this purpose: to become a place where women artists can show their art while raising awareness about social issues confronting women in Kosovo. This also allowed for a space where patriarchal discourses about feminism could be deconstructed, and where visitors could learn about feminist practices without stigma. On this note, Zana Hoxha, founder, and artistic director of FemArt, stated that organizing festivals “creates this safe and creative space not only for artists but also for the community. It is a great and unique opportunity to break the barriers of what feminism is concepted by the community.”

At the same time, for many activists in the region, art was also an agency channel and a place for healing. While it was through feminist expressions of art that many activists and artists were able to speak about traumatic events, they also relied on art as a safe space during times of war when other forms of resistance became impossible. During the festival, I was moved to tears every time I listened to each of the anti-war activists’ stories, and found out more about how they – often with others – resorted to artistic expression as a safe haven while the world was falling apart around them. Remarkable to me were two panels from the festivals: the first one’s title was Beyond Prejudice: Empowering Women to Overcome Stereotypes in Art and Cultural Decision-Making, during which I had the opportunity to hear Zana Hoxha, Arta Balay, Kshama Batya, Dijana Milošević and Besa Luzha; during the second, Peace and Security: Overcoming Fear and Building Resilient Communities, Lepa Mladjenović, Igballe Rogova, Jadranka Miličević, Ines Leskaj and Jelena Memet shared their stories with the audience.

Here, I would like to cite some of the many initiatives I heard during FemArt 11 where art was used as a way of resistance, as well as a place of peace. Besa Luzha, Music Teacher Trainer and Music Festival Manager recounted how she organized a music concert for peace, tolerance, and democracy during the year of 1999 in Prishtina, amid the war in Kosovo. Igballe Rogova, the Director of Kosovo Women’s Network, recalled how she built music “from one checkpoint to the other”, and how using music to work at a refugee camp in North Macedonia gave her and other women the power to survive. Dijana Milošević, director of Dah Theather, shared her initiative to set up a theater to deal with the burning need to handle questions of responsibility and guilt coming from feminists in Serbia, and build a feminist space where, even amid conflict, seats for peace could be placed. In the evening, La Chica’s concert also spoke to me: as I sensed every emotion in her voice while she sang about her life in Venezuela, her family, and her personal story of liberation from pain, I felt once again connected with my own home country.

FemArt also portrayed numerous other instances where women dared to burn their fear away by being together. The play Devojčice was centered around the stories of a group of girls who embarked on a journey towards their awareness about prejudices and stereotypes they faced while growing up, and their incipient revolt against crystalized and pervasive patriarchy. On a similar note, Biba May – No More also sheds light on the collective empowerment of women with disabilities and special needs, as well as advocates for equality and justice while keeping difference in mind. Another topic of discussion was women’s protests and mobilization against anti-gender governments and the curtailing of their rights: Women and Life raised attention to alarming recent changes in the Abortion Law in Poland, making abortion illegal in almost all cases.

During my free time, I took the chance to walk around Prishtina with Jadranka Miličević, co-founder and director of Fondacija CURE. While in the city center, we paid attention to details that showed signs of care from the city toward its citizens. For example, we were joyfully surprised by how many public benches we could see in the pedestrian streets! Nothing similar in Sarajevo or Belgrade! We also visited the Heroinat Memorial, the only site in the region dedicated to raising awareness of the contribution and sacrifice carried out by women who had been raped in wartime by the Serbian military and police, between 1998 and 1999. This memorial also contributes to deconstructing the emphasis on women as victims: rather, they are perceived as heroines. Although there has been little accountability when it comes to prosecuting gender-based sexual violence crimes before and during the Kosovo war, women’s organizations have been fighting for years in Kosovo to demand answers to such violations.

While efforts from women’s organizations took different forms, one important initiative was to argue for the implementation of the UN Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security, adopted by the Security Council in 2000. Indeed, the release of the book Facts and Fables on 1325 by the Kosovo Women’s Network reflects this ongoing effort. On the same note, FemArt was also the outcome of feminist actions to encourage activist and artistic responses to deal with the past and challenge the current situation of women in the Kosovar society, still pervaded by gender-based violence and patriarchal norms. While being a reminder of feminist solidarity over time, the festival showed how politics of location have not let anti-war activists forget the need to care for one another. Only through these expressions, feminists could find spaces where they could build bridges together, connect with each other, and empower themselves towards change.